(Part Five of the Clementine Paddleford blogs)

By the end of the 1920’s, Clementine Paddleford’s name was not only familiar in journalism circles, but the fame and fortune she dreamed of as a young Kansas farm girl were soon to become a reality, and she was barely thirty years old. In our present culinary world, food writing, food shows, cooking competitions, and celebrity chefs are all the rage. In early 1930’s America, food writing was not seen as the art it is today. Newspaper food articles included some restaurant reviews and a few recipes. Food coverage was more on the scientific and practical side, and definitely lacked fun and passion. Clementine knew she could do better and wanted to lure her faithful readers into the kitchen to see what they were missing. With her job as women’s editor at Farm & Fireside, reader response increased by 179% in just a few short years and she was ready to move on to even higher challenges.

Clementine was hired to begin a women’s section at the Christian Herald where she had access to a test kitchen. In her first five months, Clementine wrote forty-three feature stories, including many about church suppers. The paper also decided to pay readers $25 for their supper menus and used brand publicists and home economists as the judges. This may have been Clementine’s first time using the idea of recipe contests to lure readers. Not only that, it engaged the judges so much, that they decided to slip in their own test kitchen recipes into the mix. This gave Clementine the idea to ask the readers to “judge the judges” of a church supper contest. By including the brand publicists, Clementine not only was able to make the public happy by winning some cash, but the publicists were thrilled to have their product brands introduced to the masses. Hmmm… sounds like the inner workings of social media today! As you will read along the way, Clementine was visionary in her sense of what people enjoyed to read about food and improve their cooking skills.

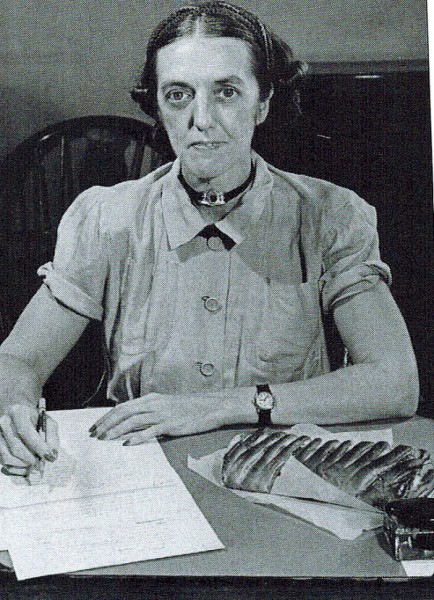

Clementine’s food writing pulled readers right into her own world of making cooking a pleasure rather than a daily task. She included details, talked of her own family traditions, and would come up with new ideas such as paying homage to Charles Dickens in her Christmas menus. Everything Clementine wrote about was fun and new, which led to many lucrative freelance writing assignments. Just as Clementine’s bright future was at a runaway pace, she began to feel some sort of chronic throat problem. Thinking it was simply her workaholic style and little rest, Clementine initially ignored it, thinking the condition would go away eventually. Sadly, it was not the case. At age thirty-three, Clementine was diagnosed with throat cancer, and in the 1930’s, the odds were poor for survival. Clementine was basically given a death sentence. But as you have probably guessed, Clementine was not one to quit. Her best weapon against the cancer was all she knew – ambition and work. Given a choice by her doctors of removing her larynx and vocal chords, she would never speak again. The second option was to remove only the infected parts, which only a handful of physicians performed and was far riskier. Without hesitation, Clementine opted for the latter, as she couldn’t imagine life as a reporter who could not speak. However, Clementine did have to endure having a tracheotomy tube to replace the larynx, which aided in speech and breathing. For the rest of her life, Clementine had to push a button on the throat tube to speak. In order to cover up the tube, she had to change her wardrobe, and in her own mind, become even more charming and charismatic than ever to divert people’s eyes from her throat to her eyes. Photos of Clementine in her remaining years showed her camouflage of a ribbon choker around her neck and also the use of dramatic scarves and capes. Her deep and throaty voice made it sometimes difficult for others to hear her, but Clementine used all her charms to move beyond it. She even declared it to be an asset in the long run, because she said that now, “people will never forget me.”

First known photo after throat surgery

Even though it must have been very difficult for Clementine to adjust to her new way of communicating, she threw herself into her work even more. During this time, Clementine formed a strong bond with the New York Herald Tribune and its weekly Sunday magazine insert, This Week. Clementine found herself with a bright and modern test kitchen from which to work. She persuaded her boss to let her start a “market” column, writing about seasonal produce and the specialty food shops. (See? Ahead of her time once again!) Clementine would run around New York City, comparing freshness and prices, then run back to the office and write her column. At the time before Clementine’s employment, the kitchen would receive around 6,000 calls per month with various questions. After only one month of Clementine’s input, the calls reached almost 7,500. By the first year, calls went from 28,000 to 78,000. Singlehandedly, Clementine made it happen, not to mention she still continued her freelance work writing for Better Homes & Gardens, Ladies Home Journal, and many more. Clementine had definitely made a huge name for herself in the industry, and now more than ever, decided to “hit the road” for even more stories, thus becoming our first traveling food writer.

Up next: The sights and smells of our country become Clementine’s passion.

Never knew about Clementine–fascinating

Yes, Clementine is definitely fascinating. I can’t wait to get back to the library at Kansas State and study some more. I only touched the tip of the iceberg!

Well written, interesting to learn about her.

I had never heard of Clementine either! What a strong person with passion and perseverance – inspirational!

Thanks for sharing Debbie ( :